Case study: bringing 360° photography to CarMax

An excerpt from a case study I wrote for Jim Kalbach's "The Jobs to be Done Playbook" (Rosenfeld Media 2020)

“Could you look at another picture?”

The research participant clicked the “next” arrow, and an image of a car for sale appeared on the screen in front of them. The room stayed silent for a moment.

“This is, um, a nice photo,” the participant said. “I like that you can see how clean the seats are. That’s...nice.” The participant clicked the arrow a few more times, pausing every few seconds, trying to come up with something more to say.

It was clear from this research session, and many others like it, that we had hit a wall. I was part of a team at CarMax that was responsible for presenting our used car listings online, and ensuring we were displaying our cars with the best photography possible. The problem was that we had run out of tangible ways to make the photos better.

"CarMax wows customers with new 360º photography experience – 'it's like i'm at the dealership!' says CarMax shoppers"

-PR Headline

This type of photo was the one I discovered Car Shoppers spent the most time looking at. When I began asking "why," it led to the insight that customers primarily use photos to determine what options the car comes equipped with.

To help influence stakeholders, I stitched together a highlight reel of customers experienceing 360° in a prototype. The video (titled "360 freakout") enabled the team to secure resources for our first in-store pilot.

We were doing all the things we were told to do in today’s age of technological disruption: constantly talk to our customers, experiment our way to the best version of the product, and always move fast. But no matter how good we were at embracing these values, none of the methods we were using seemed to be producing results anyone would consider meaningful. We would bring in people who claimed to be in the market for a used car and try to learn how to improve the photo experience based off of the feedback they gave. Then we would implement changes to the experience, only to see little to no noticeable impact to our business metrics.

It wasn’t until I came across JTBD, or the “Jobs to be Done” theory that our team began gaining traction. After diving into the material, I realized that we weren’t paying enough attention to understanding the underlying needs that would make customers turn to photos. Our focus was purely on how to improve the cosmetic attributes of the photos – i.e the quality of the photo, the angle, whether it was best to shoot indoor or outdoor, etc. Instead, I realized we should be focusing on how useful the photos were in solving the jobs in people’s lives. What we were doing would have been akin to a team of engineers deliberating on what color the fins of an airplane should be instead of figuring out how to make it aerodynamic.

I took this line of thinking back to my team and posed the question to them. “Maybe we’re looking at this the wrong way. What are the jobs that people are hiring photos for? What are people thinking when they turn to photos?”

Instead of asking people for what they desired, we observed how they used our product, and examined their motivations that drove their behaviors. Instead of speaking to anyone who said they had vague plans to purchase a car in the near future, we selectively chose to speak to people that had recently purchased a car. This way, research participants were able to reflect on the choices they made during the shopping process, and show us their thinking behind it, instead of performing hypothetical scenarios in front of us.

Once we started focusing on what caused people to look at photos of a car, our research started producing many more fruitful insights. Now attuned to looking for the motivations that were driving behaviors, we quickly began seeing patterns.

One of the first patterns we noticed initially had us puzzled. As car shoppers would look through photos of a car, many would slow down to one photo – a close-up shot of the steering wheel of the car. They would spend several seconds intently studying the picture. Some would even zoom into the photo, or lean their head forward to try to get a better look at the steering wheel. When we asked people what they were doing, they replied that they wanted to see if the car was equipped with Bluetooth, a feature that enabled hands-free calling. To them, looking at a picture of the steering wheel was the best method to determine whether or not the car had Bluetooth, as a car with this feature would have a button to answer the phone on the steering wheel.

Our team was surprised by this, because the car detail page had a section devoted to listing out the features and options the car came with. But as we learned from multiple interviews, car shoppers didn’t want just a list of options and features, they needed to see the feature in order to feel confident that this might be a car worth purchasing. In other words, these car shoppers had a job in mind (find a car with Bluetooth), and to them, hiring a photo of the steering wheel was the best solution.

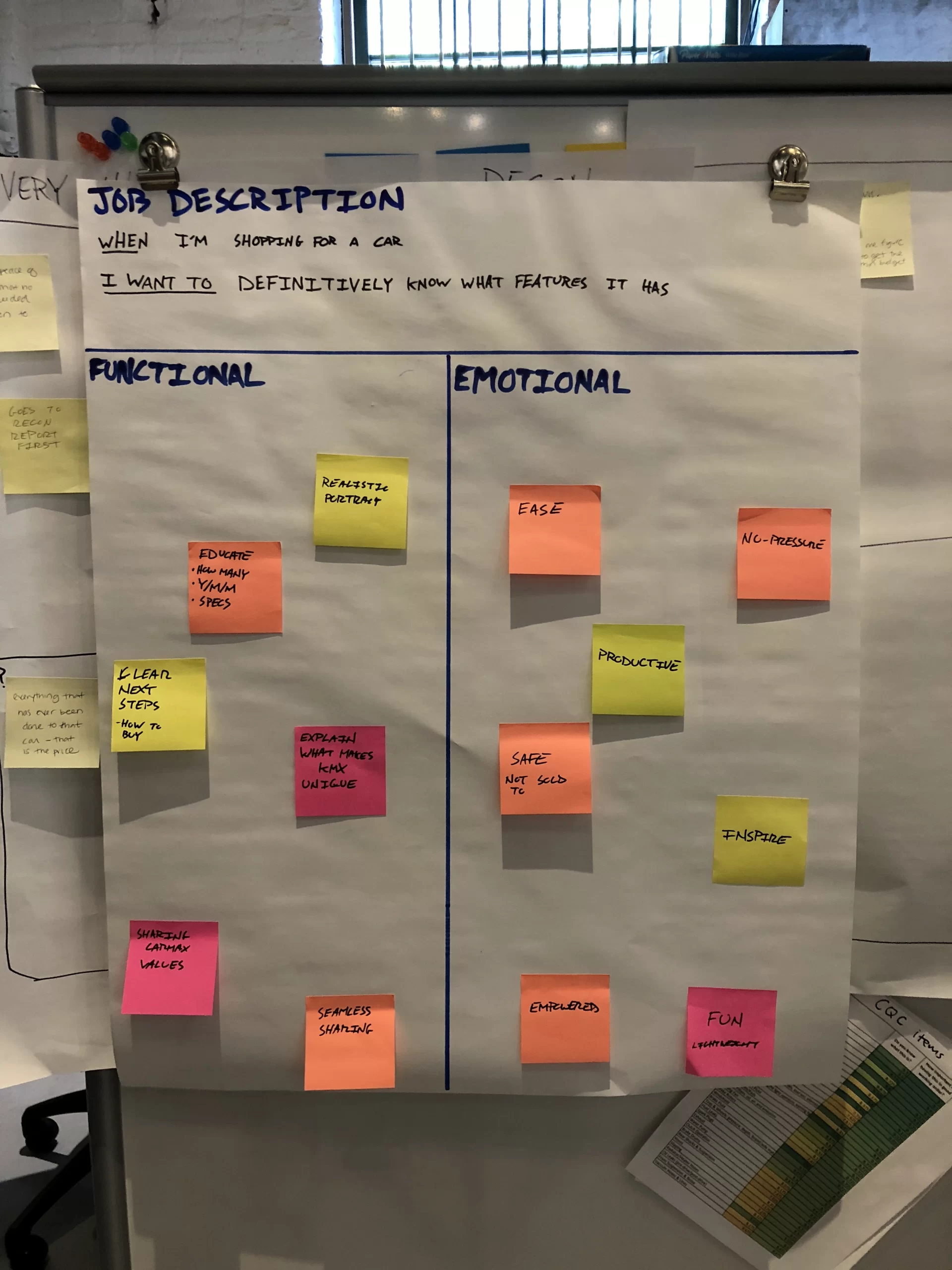

Once our team uncovered this job and the motivations behind it, we asked ourselves how we could design an experience that would better serve the job. Taking inspiration from a passage in Daniel Silverstein’s “Innovators Toolkit”, I created a one-sheet activity called the “Jobs to be Done Canvas.” The canvas clearly defined the job at the top of the page, then split the requirements of the solution into two halves: the functional and the emotional.

Gathering the core team into the room, we filled the boxes based off of what we learned from customer interviews. At the top of the sheet, we defined the job: “When I’m shopping for a car, I want to definitively know the features it has.”

In the “functional” box, we listed the tangible outcomes the solution needed to accomplish to satisfy the job. Team members would write ideas on sticky notes and add them to the canvas, like “show the feature, don’t tell it” and “easy findability.” On the other side of the canvas, we listed the “emotional” requirements, or how the customer should feel during and after the solution. During interviews, participants would tell us they wanted to feel absolutely certain that the feature was on the car, so we put things like “confident” and “assured” in the box.

By the end of this exercise, we had a single sheet we could turn to in order to understand the job and the requirements of the solution. This canvas became a living document that captured our findings in real time. After completing interviews with new participants, we would debrief in front of our JTBD canvases and make additions to the functional and emotional requirements based off of what we just learned.

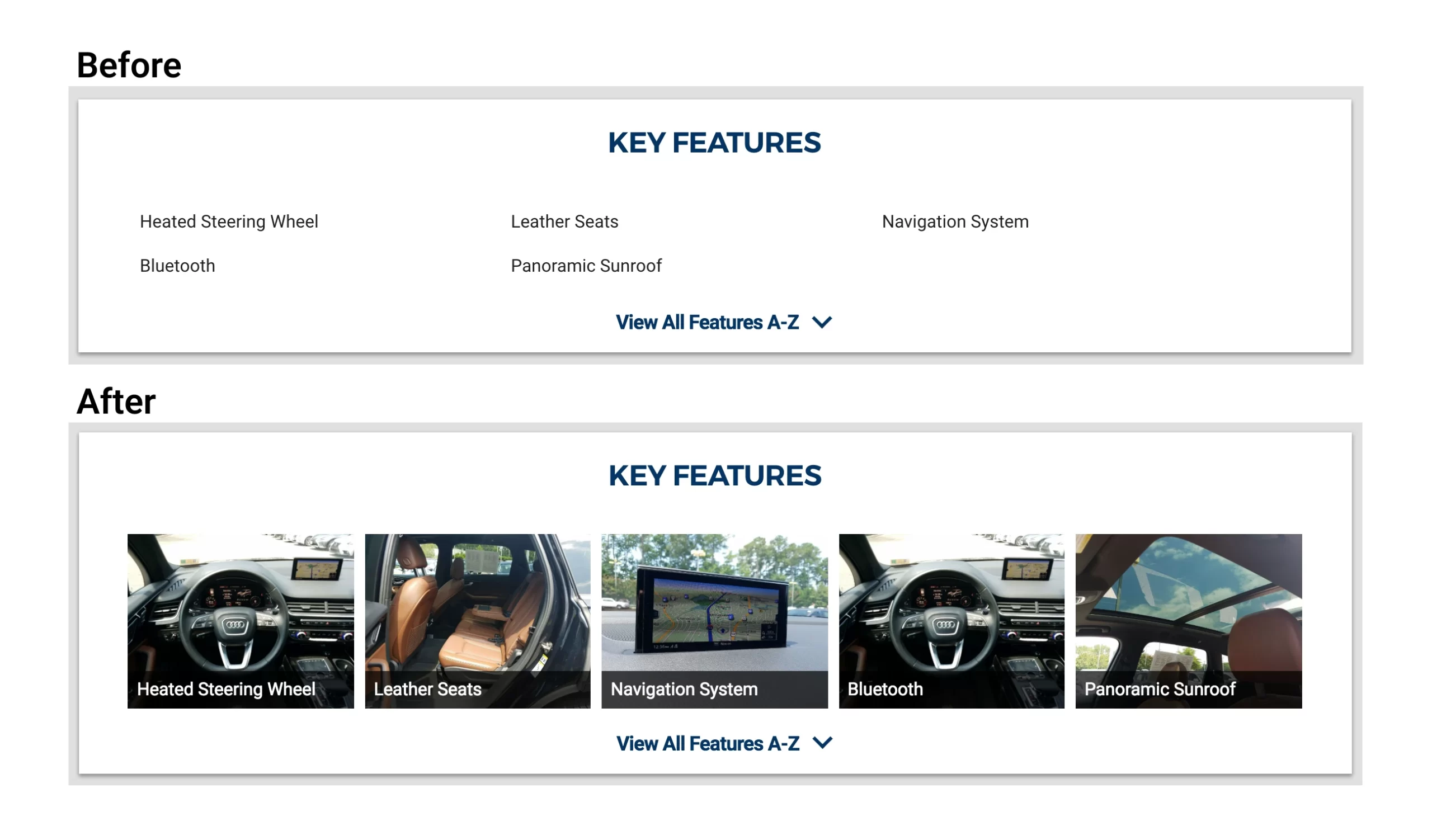

Before and after of the "Features" card on the car detail page. Including images in this section dramatically increased conversion to submitting a lead.

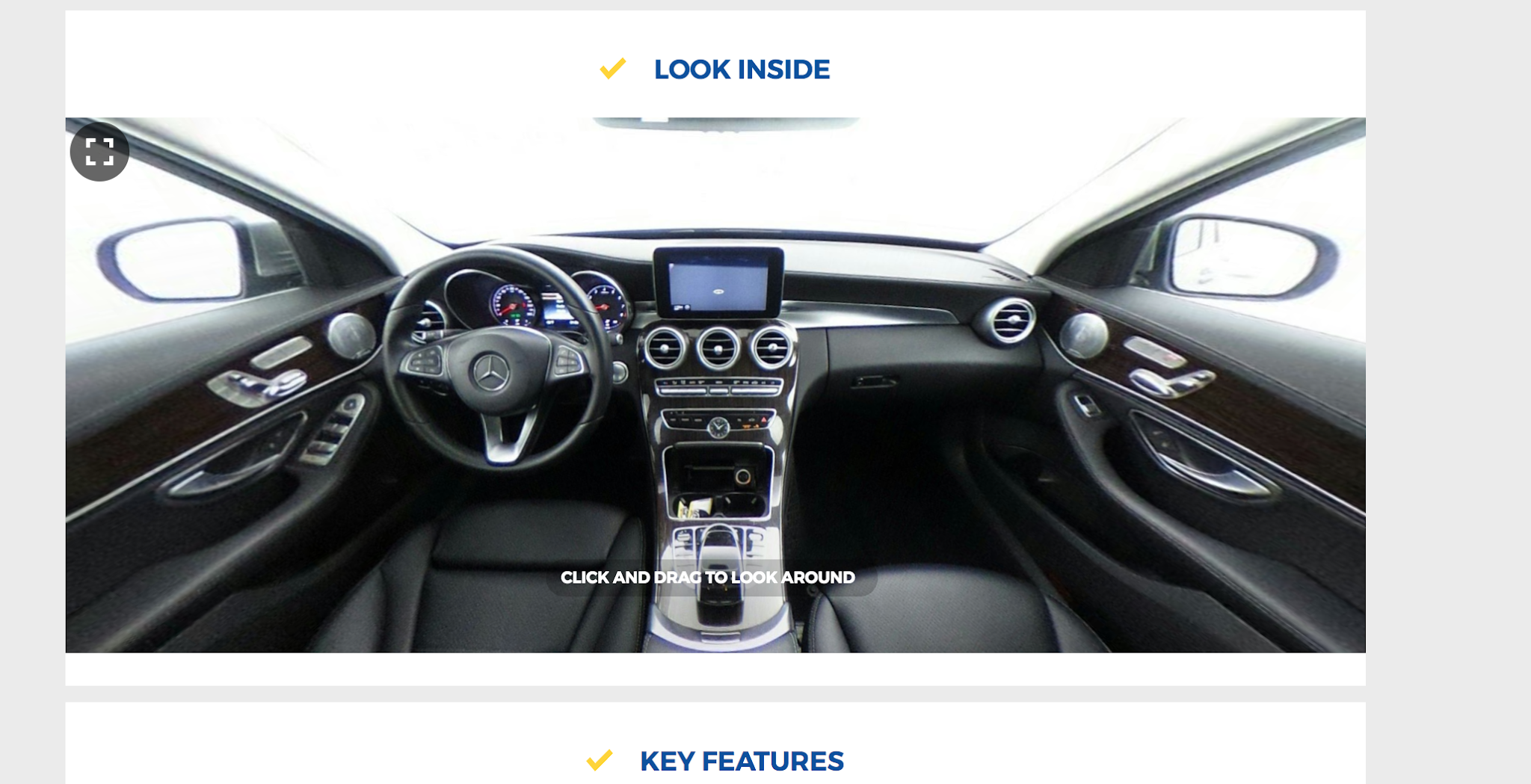

With this job understood, we launched a small change to the car page that produced a big result. Instead of providing a text list of the features on the car page, we displayed a series of thumbnail pictures of what the features looked like. This prevented people from having to hunt through all of the pictures of the car to try to find one particular feature, while also giving them the confidence that only a visual confirmation could provide. By satisfying one of the jobs that car shoppers had when they visited carmax.com, we were better able to serve their needs, and thus make them more likely to purchase a car from us. Our business metrics increased when we split site traffic during an A/B test of features displayed in pictures versus the old way. Energized by seeing the possibilities of designing for jobs, we continued using the framework and the JTBD canvas to uncover more customer insights. After launching the improvement in how we display car features, our team uncovered another job during customer interviews: understanding how big the car is. After looking through our analytics and noticing that a collection of interior shots of the front and back seat were highly engaged, we decided to dive deeper and understand why. We learned that these photos were valuable to shoppers trying to figure out how big the interior of the car was. Pictures, shoppers would tell us, gave them a better sense of the size and layout of the car better than other methods, like looking up the specifications or the cubic square feet. While this was a good solution compared to the alternatives, it still wasn’t perfect.

Knowing now what we had learned from our first discovery of the unmet jobs on the car page, we recognized this as another opportunity to design for the job. We ideated our way to a new solution: a 360 degree photo of the inside of the car. This solution proved popular in testing, and the team quickly worked to implement it in all of our stores.

JTBD proved to be a radical mind-shift in how our team worked. We stopped trying to make shallow improvements to the interface, and instead went deep to understand the motivations that drove shopper behavior. Thanks to JTBD, our team was able to focus on solving the biggest opportunities to the customer experience on Carmax.com, thus making a meaningful impact to the product.

Selected Works

CarMax Capture AppProject type

Docusign Joint AgreementsProject type

Case study: bringing 360° photography to CarMaxProject type

AI Agreement Comparison PrototypeProject type